The Politics of Women’s Insecurities: How Your Doubt Feeds the Patriarchy.

A personal and political reckoning with the world’s obsession with women’s appearance and how much it costs us.

In our world, the kind of beautiful a woman should be is the kind that is complete; where you tick ALL the boxes of physical features preferred by a group of men turned majority. And the worst kind of beautiful you can be is the one accompanied by the conjunction ‘but’. “She’s beautiful but…” They hated this kind so much they coined a new word for it: ‘mid’. I was 9 when I realized that my beautiful wasn’t the perfect kind. I was beautiful but…

My uncle took a long look at me and called me “bottle” because I had no hair on my legs, and in our culture, being hairy is one of the beauty standards. I was only 9, but I had just received my first lesson on how I had fallen short of being “completely beautiful”. I was confused too because in the American TV shows I watched, girls spent time shaving every visible strand of hair on their bodies to look the way I was being mocked for. I guess that was my second lesson: beautiful there, but not beautiful here. That lesson lasted long enough for my American TV-watching brain to realize all the other features I lacked which made me not “completely beautiful” in America too. My Afro hair, flat nose, and non-blue eyes stared back at me in the mirror, and I saw that I looked nothing like the girls who were beautiful in America. Not completely beautiful here, not completely beautiful there.

I almost became the perfect kind of beautiful (in my culture, at least) when I hit puberty and hair started to grow on my legs. I was elated and could hardly believe it until I slipped back into my shorts and stepped out into the world. The stares told me I was a little too late; the world had moved on, the American beauty standard was in, and I needed to carefully strip my legs of every strand as if I was defeathering a chicken.

Looking back now, this should have been the point where I realized the arbitrariness of beauty standards.

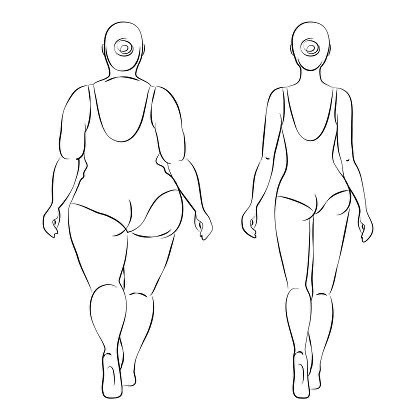

My most valid proof of the arbitrariness of beauty standards is more recent. It began with celebrities surgically altering their bodies to have thinner waists, more rounded hips, and bigger butts. Reality stars like Kim Kardashian were at the forefront of this new trend, and other elite women followed suit, churning out thousands of dollars to transfer fat around the body in order to achieve the reigning ideal body. Curvy Black women who had always been at the bottom of the Western beauty hierarchy were finally having their moment. Their bodies, like those of their mothers before them—which had previously been described as too fat, unhealthy, and often overtly sexualized—were, all of a sudden, the ideal body type for all women to have.

BBLs began its early glory days between 2007 and 2010 and was mostly done by famous women. However, over the next decade it became increasingly popular and even more accessible that ordinary women could save up money and have the surgery done in their home countries. Actresses, singers, dancers, reality stars, bankers, entrepreneurs, retail workers, women of different ages, nationalities and backgrounds were getting BBLs. In fact, there were cases of fans questioning their favorite stars who had not gotten BBLs or liposuction. The glorification of curvier bodies and bigger butts was now in full swing and it has become a trend women who care about desirability and who have the means have either jumped on or considered.

Not until 2022, when the harbinger of beauty standards, Kim Kardashian, showed up to the MET Gala looking thinner than usual and with a noticeably smaller butt, did people start to wonder if the era of BBLs had come to an end. In the following weeks, her sister Khloe also debuted a new thinner look, and that was all the confirmation the world needed to confirm the advent (or re-advent) of the skinny era. There were speculations that the new bodies were the result of a diabetes medication called Ozempic. Some others were convinced they intentionally removed fat from the areas they had previously transferred to. Whatever the means, one thing remains clear: skinny bodies are back in vogue. Between 2022 and 2025, we’ve seen several curvy celebrities, even those who had previously been the voices of the body positivity movement, lose a lot of weight in a very short period of time just to jump on this new thinness trend.

Where does that leave the women who spent thousands of dollars to get the “ideal” body?

But most of all, where does that leave the Black women whose bodies were idealized and now un-idealized?

To be a Black woman in these times is to have been born into a world that disqualifies you from every attempt at being beautiful, only to turn around every couple of years to steal a physical feature of your Blackness and glorify it only when it’s on the bodies of women who look nothing like you. Having a single feature glorified but your entire existence rejected is the reality of most Black women navigating the world today. We are forced to make peace with the fact that certain aspects of our bodies are just a trend for other women to appeal to the desirability politics of the time. It happened with our full lips. It happened with our curves. And now, we wake every day wondering: what are they coming for next?

The randomness of it all is upsetting. Today, the world expects women to look a certain way and tomorrow we are expected to look a completely different way. One terrifying aspect of these heinous beauty standards is that you find women who you think should know better subscribing to it under the claim that they are doing it for themselves. I refuse to buy into that logic until someone explains to me how getting a BBL improves a woman’s life (in a way that doesn’t involve or revolve around men). However, I am slow in my judgment because I am aware that women are taught from an early age to prioritize being chosen by men by looking and acting only in ways that appeal to existing standards. It requires years of unlearning and coming to terms with the truth of it all.

This is the truth of all beauty standards: a group of men take their personal preferences, turn them into benchmarks, some women “qualify”. Those who do not qualify buy into it anyway, and millions of women who look nothing like the ideal are forced to sulk, shrink, and starve.

This would have been an easier conversation to have, one where we talk about how to navigate the difficulties of being a “beautiful-but” woman, if the world was not so wicked to women it does not consider beautiful. From TV to billboards and even social media, women who do not meet the beauty benchmarks are constantly reminded that they do not belong. When a woman—after years of unlearning and dismissing what she’s been taught—thinks she has conquered that need to measure up and takes the first bold step of posting a picture of herself, she is in many instances met with so much vitriol from people who do not think that she deserves to take up space because of the way she looks. Cloaked in the vitriol is: “how dare you show up looking different from what we have entrenched?”

The patriarchy demands that you exist in hiding, constantly cowering in shame and possibly performing gestures of apology for not meeting its ridiculous standards, but this is where you reclaim your power. You must starve it. The main purpose of beauty standards for women in a patriarchal society is to serve as a distraction. It needs us to be so busy figuring out how best to appeal to the male gaze or brooding over not being desired that we forget that we live in a world that has systems in place to ensure the subjugation of women. Our world today is filled with brilliant and exceedingly talented women who are afraid to take up space because they feel insecure that they don’t have slim waists, big butts, button noses, or any of the other features the patriarchy demands from women. We have been robbed of an enormous amount of female excellence, and all of that can be attributed to the politics of desirability.

There is another side of this coin not often talked about: that majority male attention can also serve as a form of distraction to conventionally attractive women. Some women who meet all the requirements of beauty standards often have to deal with unwanted attention from a young age, and this could result in a struggle to define themselves outside their attractiveness, forgetting that there could be so much more to being a woman than just being beautiful. In some instances, these women go through life with unrealized potential, never knowing what else they could be besides beautiful. With the reemergence of trad wives, the pipeline from pretty privilege to a kept girlfriend and then to a stay-at-home wife with unrealized potential has never been more straightforward. Both sides of the coin of beauty standards are harrowing, and I sometimes think of it as a house slave–field slave situation in which they are all still slaves anyway. The broad feminist movement suffers regardless.

The other purpose beauty standards serve in this patriarchal world is the silencing of women. Oftentimes, when women do not measure up in terms of beauty, that self-doubt spirals into other areas of their lives; they begin to doubt their ideas and opinions, forcing them into silence. We’ve seen the world make scapegoats of non-conforming women who dared to speak up. Because beauty is a currency for attention and consideration, women who do not have this currency are given no audience. The silence for some of us is learned through observation—watching what happens to women who dare to speak without being a complete kind of beautiful. The system gains immensely from the silence of women; women who feel insecure never feel good enough or deserving, leaving space for lesser qualified men who are born with the pre-packaged confidence of a world that prioritizes their success to take up. Our silence presents the patriarchy with a needed opportunity to reassert itself, so we must deprive it.

Women are major revenue sources of capitalism. The cosmetic surgery industry is heavily funded by women’s insecurities. According to Straits Research, the global cosmetic surgery and procedure market size was valued at USD 156.39 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 185.67 billion in 2025 and USD 419.97 billion by 2033, exhibiting a CAGR of 14.70% during the forecast period (2025–2033), and the female segment is the largest revenue contributor to the market. What this means is that women are spending billions of dollars to get slimmer jaws, breast augmentations, nose reshaping, liposuction, just to fit into the prevailing beauty standards that serve no other purpose than appealing to the male gaze. Women who make money in spite of a system set up for them to fail spend said money on optics to appeal to the enablers of that system. What a sad story!

There are manifold reasons women who get these procedures often give, and an ideal response to them should always be: why?

“I don’t like my nose” why?

“I just wanted a slimmer waist” why?

“I hated my hip dips” why?

“My partner said I should get it done” why?

If we do not learn to interrogate our insecurities, both as individuals and as a collective, we will always end up right where we started. There’s a level of truthfulness required before unlearning happens, and if we do not reach it, we have failed before we even started. An approach I have taken towards my insecurities is to question them, and at the end of it, any insecurity which is fueled by what men may not find attractive is pointless. I have no use for it, and you should have no use for your personal insecurities which center male preferences.

The arbitrary nature of beauty standards should teach us one thing: that they are engineered by men based on whims and serve no purpose. Who gets to be seen as beautiful, who gets loved, and whose bodies are considered worthy of intimacy should not be decided by a system which does not respect women.

I, for one, will only like to be the kind of beautiful decided by feminist women